The American side is "risking" confrontation with "de-risking"

Editor's Note: The following are excerpts of a recent interview with U.S. scholar, James Deshaw Rae, also professor of politics at California State University, Sacramento, on Washington's "de-risking" of China and its implications for the global economy and stability .

Q1: "De-risking" has become a novel buzzword in discussions surrounding US-China relations. Recently, the U.S. side has expressed its intention to "de-risk and diversify" its relationship with China, not decouple. Some Chinese individuals express concerns that "de-risking" might be just another form of "decoupling" aimed at shutting China out and containing its growth. How would you respond to these concerns?

James Deshaw Rae: De-risking seems to be a slower paced form of decoupling. The American bipartisan consensus which has turned so hostile to China in the past few years on a variety of issues has seemed to coalesce to reducing American dependence on manufacturing and production in the Chinese mainland and at the same time limiting Chinese firms ability to access certain strategic resources, including microchips which fuel technological functionality and innovation. American foreign policy seems to be directing investment away from China to other markets and suppliers, and obviously leveraging U.S. influence to try to persuade other countries from downsizing their reliance on Chinese private and state sector firms. Thankfully, the Biden team recognizes that decoupling is virtually impossible, and that "de-risking" itself could have negative repercussions for the United States and the global economy. Certainly, if China chooses to adopt reciprocal instruments, we could once again face the possibility of an open trade war. The American side is "risking" confrontation with "de-risking".

Q2: The United States used to champion globalization and free trade, encouraging others to open their doors and become part of the world economy. What, in your opinion, has led to the shift for U.S towards a more inward-focused approach?

James Deshaw Rae: The Trump administration made protectionism possible, breaking with nearly a century of American support for free trade and multilateralism. This populist economic message plays well in the American rust belt of the industrial (now largely de-industrialized) upper Midwest, where working class voters decide American elections in swing states like Michigan and Pennsylvania. The hollowing out of the American middle class and dependence on overseas imports has become quite political, and both American political parties can hope to tap into that resentment and play the "China card". The Americans also recognize their neoliberal form of economic ideology has largely failed to keep pace with East Asia's state-led development model, and under the Biden team seeks to replicate some of the top-down directed planning employed so successfully by China. Thus, the U.S. has stepped away from its long time role as champion of the international financial institutions and the free trade regime, leaving space for others to assume greater responsibility but also potentially leading to more beggar thy neighbor policies arising from economic nationalism.

Q3: When put in the perspective of economic globalization, how might the United States' "de-risking" from China negatively impact global industrial and supply chains? What potential disruptions and challenges could arise as a result?

James Deshaw Rae: China has built of the most flexible and productive work force probably in world history, cultivating extraordinary human capital and infrastructure development, notably rail and shipping. The world’s supply chains still depend on China, particularly its southeast. China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is also part of the lifeline of economic production across the Global South. The world economy needs a strong and prosperous China as focal point of global supply chains and investment, but also it’s growing consumer economy to be at full capacity to stimulate growth globally. The world needs China.

Q4: Looking beyond trade, what do you consider potential impacts of whether the United States calls it "decoupling" or "de-risking" from China? How might these actions impact areas such as technology, investment, and global cooperation?

James Deshaw Rae: American efforts to limit China's economic expansion have jeopardized firms such as Huawei and perhaps entire technological sectors of the economy. China will have to seek to further develop independent domestic production, while maintaining outlets and linkages with friendly countries and key strategic countries like India that face American pressure to avoid the isolation experienced by Russia in recent years. This also creates some diplomatic vulnerability, but China faces essentially no enemies in the world, fortifying positive relationships with India and Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and Iran, Russia and Ukraine, etc. Countries don’t want to have to choose.

Q5: In your view, what is the real risk to global economy and stability?

James Deshaw Rae: Any form of U.S.-China de-risking is going to slow growth, inhibit supply chains, and create economic and political uncertainty. The economic size of the Euro-Atlantic region pales in comparison to the dynamism of the Asia Pacific region. Sino-American interdependence is too big to fail. The world economy needs a healthy China and America, and they are fitter when they integrate their economies, which have so many natural symbioses and mutual benefits.

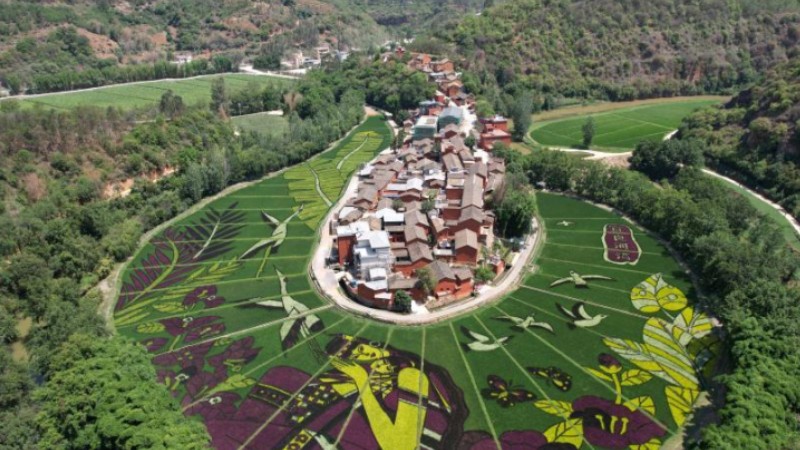

Photos

Related Stories

- A US puppet

- Sino-US ties at a new 'crossroads'

- Envoy: Sustain good momentum

- China-U.S. climate dialogue held in Beijing

- Senior Chinese diplomat meets with Henry Kissinger

- Diplomat: US needs Kissinger-style wisdom

- China-U.S. economic, trade ties as inseparable as "threads and needles": Chinese diplomat

- Chinese vice president meets U.S. special presidential envoy for climate

- Chinese defense minister meets with Henry Kissinger in Beijing

- Country's path of peaceful development boon for world

Copyright © 2023 People's Daily Online. All Rights Reserved.